- ResiClub

- Posts

- Trump directs Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to buy $200 billion in mortgage bonds to attempt to push mortgage rates lower

Trump directs Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to buy $200 billion in mortgage bonds to attempt to push mortgage rates lower

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac have already started to accelerate their retained mortgage holdings—with them rising around $69 billion in the second half of 2025.

Today’s ResiClub letter is brought to you by Lennar Investor Marketplace!

When you invest with Lennar, you’ll be connected with reputable property managers who handle tenant placement, repairs and ongoing maintenance. Lennar partners with experienced and qualified property management firms nationwide. Through these partnerships, you can access pre-negotiated rates that average between 6% and 6.5% for the base property management fee, compared to the standard average of about 10% for individual investors. Additional benefits include waived management fees for the first few months, significant savings on leasing and renewal fees, and expert guidance in choosing the best management firm for your property.

Join today to unlock your access to Lennar’s exclusive property management partnerships.

Trump directs Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to buy $200 billion in mortgage bonds to attempt to push mortgage rates lower

On Thursday, President Donald Trump announced that government sponsored enterprises (GSEs) Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac will buy an additional $200 billion in mortgage bonds.

“Because I chose not to sell Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in my first term, a truly great decision and against the advice of the “experts,” it is now worth many times that amount—an absolute fortune—and has $200 billion in cash. Because of this, I am instructing my representatives to buy $200 billion in mortgage bonds. This will drive mortgage rates down, monthly payments down, and make the cost of owning a home more affordable.”

Long-term yields—like the 10-year Treasury yield and the average 30-year fixed mortgage rate—are set by demand / lack of demand for the underlying bond. Yields move inversely to bond prices. If demand for long-term bonds rises, prices go up and yields/mortgage rates fall. If bond demand falls, bond prices drop and yields/mortgage rates rise.

For example, when the Federal Reserve engages in quantitative easing, as it did during the pandemic, it buys long-term assets like Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities (MBS), increasing bond demand and pushing bond prices up and long-term yields down, including mortgage rates. The Fed’s MBS purchases put additional downward pressure on mortgage rates in 2020 and 2021. Conversely, during quantitative tightening since 2022, the Fed has been letting MBS assets roll off its balance sheet without replacing them—effectively removing a major MBS buyer from the market—can put additional upward pressure on 30-year fixed mortgage rates.

Effectively, Trump is proposing to use Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac—both in government conservatorship—to absorb a larger share of mortgage bonds, increasing relative market demand for MBS. That could put some short-term upward pressure on MBS prices and downward pressure on mortgage rates, further reducing the “mortgage spread.”

Around the same time the Federal Reserve began raising short-term rates and stopped buying long-term bonds in the spring of 2022, financial markets started pulling back from bonds, causing long-term yields—including mortgage rates—to surge. Only, without the Fed buying MBS, the 30-year fixed average mortgage rates saw a bigger jump than the 10-year Treasury yield.

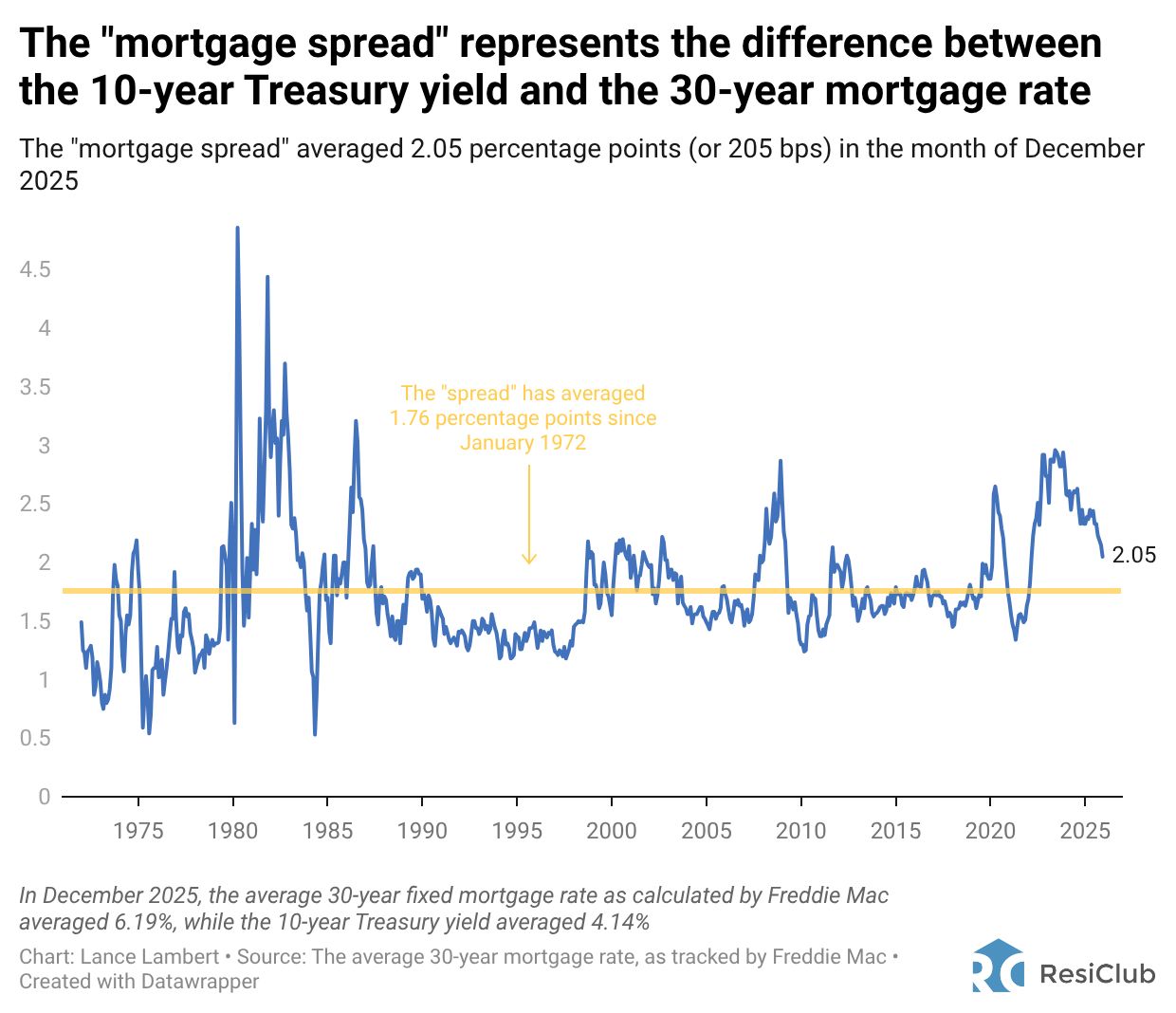

At its peak in June 2023, the “mortgage spread”—the difference between the 10-year Treasury yield and the average 30-year fixed mortgage rate—hit 2.96 percentage points (296 bps). That was far above the 1.76 percentage point (176 bps) historical average since 1972.

Over the past 2 years, the “mortgage spread” has slowly compressed—hitting 2.05 percentage points (205 bps) in December 2025.

The goal of Trump’s announcement on Thursday (i.e., Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac buying an additional $200 billion in mortgage bonds) is to accelerate that “mortgage spread” compression.

As reported by Bloomberg in December, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac have already started to accelerate their retained mortgage holdings—with them climbing around $69 billion in the second half of 2025.

According to John Burns Research and Consulting, if Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were to add another $200 billion in mortgage bond holdings in 2026, it would put the GSEs pretty close to their $450 billion legal limit ($225 billion each).

“Fannie [Mae] and Freddie [Mac] have already added ~$70B to their retained mortgage portfolios since May of last year. Adding another $200B would basically put the GSEs at their legal cap ($225B each).”

Following Trump’s Thursday post, there was some immediate MBS pricing movement.

That said, it’s unclear exactly just how much impact an additional $200 billion in GSE retained mortgage bonds would have on the “mortgage spread” and the average 30-year fixed mortgage rate.

Through the end of June 2025, there is $9.26 trillion in agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS), according to data the Urban Institute recently provided to ResiClub. Below is the breakdown:

—> $3.00 trillion held by depositories (banks)

—> $2.74 trillion held everyone else

—> $2.14 trillion held by the Federal Reserve

—> $1.33 trillion held by foreign buyers

—> $0.06 trillion held by GSEs (Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac)

The chart below is the same as the one above, but it shows MBS holders by distribution.

Prior to the Great Financial Crisis, the GSEs (Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac) used to be much bigger buyers of mortgage-backed securities.

“For years, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were the buyers of last resort in the market, stepping in to profit from widening spreads and, in doing so, putting a comforting outer bound on MBS volatility. Once they went into conservatorship, the government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) were replaced in that role by the Federal Reserve, which stepped into the agency MBS market to calm much larger swings in the economy. All of this went unnoticed outside of the MBS market until recently, when the Federal Reserve finally ended its time in the stabilizing role, leaving the MBS market without a buyer of last resort for the first time in decades.”

“The GSEs gave up their role as market stabilizer when they went into conservatorship and began reducing their portfolio under the terms of their bailout by the Treasury. The Federal Reserve then promptly stepped into the role. As part of its broader effort to shore up the market in the wake of the financial crisis, the Federal Reserve bought $1.25 trillion in agency MBS between January 2009 and March 2010 and bought another $823 billion between 2012 and 2014. Largely because of that aggressive posture, along with the bailout of the GSEs, the MBS market and mortgage liquidity generally remained stable through the depths of the crisis, a remarkable feat given the level of dislocation in the rest of the economy.”

“The Federal Reserve was then well positioned to handle the next major disruption in the MBS market, when financial markets seized up in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. In February and early March 2020, the financial markets froze, and investors were forced to sell their agency MBS to build cash reserves, pushing mortgage spreads wider by 75 basis points. The Federal Reserve stepped in in March, committing to buying agency MBS and Treasury securities “in the amounts needed to support smooth market functioning and effective transmission of monetary policy to broader financial markets and the economy.” 1 True to its word, the Federal Reserve, over the next month, bought more MBS than the entire gross production of the securities, stabilizing spreads and, with them, mortgages rates. Spreads ultimately settled a bit higher than they had been before the pandemic, but that was attributable to volatility in fixed income and a refinance wave triggered by the drop in Treasury rates.”

“The Federal Reserve relinquished its role as the stabilizer of the agency MBS market when it pivoted to quantitative tightening in March 2022, ending its purchases of MBS and committing to running off its MBS portfolio. With the GSEs still operating under the portfolio constraints imposed in conservatorship, that left the market without a stabilizer for the first time in recent history.”

Below is Realtor.com senior economist Joel Berner’s take on the Thursday announcement by Trump.

“Details remain limited, but it’s difficult to see this proposal moving mortgage rates in a large or lasting way. A one-time infusion of roughly $200 billion, or even a series of smaller purchases that add up to that figure, is unlikely to meaningfully alter long-term mortgage pricing. When similar actions by the Federal Reserve have lowered rates in the past, it’s because markets viewed those purchases as large, sustained, and predictable. In fact, the Fed continues to hold $2 trillion of mortgage backed securities even after 3 years of reducing their holdings. Without that same level of scale and credibility, any impact on mortgage rates would likely be modest and short-lived.”

“Even if mortgage rates did dip temporarily, which could happen as MBS purchases compress the recently high spreads between the 10-year and mortgage rates, some of which we've started to see already, the resulting boost to buyer demand could put upward pressure on home prices, offsetting some of the intended affordability relief. That dynamic would likely benefit sellers, particularly in parts of the South and West where homes are spending longer on the market and price cuts have become more common. However, first-time buyers would still face heightened competition. Without existing home equity, many would continue to struggle to put together a sufficient down payment, limiting the practical benefit.”

“As with other housing policy ideas focused on demand, the larger issue is that the market’s core challenge remains on the supply side. If this move is perceived as a one-off rather than a sustained effort to lower borrowing costs, it is unlikely to change builder behavior or materially increase housing production. Without meaningful gains in construction, the long-term impact would be minimal, aside from a potential one-time boost to home prices.”

“It’s also worth noting that inflation expectations play a critical role in mortgage rates. Policies that blur the lines between fiscal action and monetary policy risk unsettling investors, which can push inflation expectations higher. This is the opposite of what’s needed to bring mortgage rates down in a sustainable way. Overall, while the goal of improving affordability is broadly shared, policies that fail to address the underlying supply shortage are unlikely to deliver meaningful or lasting relief. Sustainable progress depends on adding homes, through new construction and expanded inventory in chronically constrained markets, rather than short-term interventions that primarily shift demand."