- ResiClub

- Posts

- Tightened credit pulled Wall Street into single-family housing following the bust, explains CEO of institutional landlord Amherst

Tightened credit pulled Wall Street into single-family housing following the bust, explains CEO of institutional landlord Amherst

Amherst CEO Sean Dobson believes housing affordability would improve if some of the buyers pushed out of the market after 2008 were brought back into the fold.

Today’s ResiClub letter is brought to you by acres.com!

You optimize every cost when it comes to building, but are you optimizing the largest line item on your balance sheet?

Land acquisition shapes your margins long before construction begins. Protect your pipeline. Protect your margins. See how Acres' complete land intelligence transforms your biggest expense into your competitive advantage.

The U.S. housing market, as told by the CEO of institutional landlord Amherst

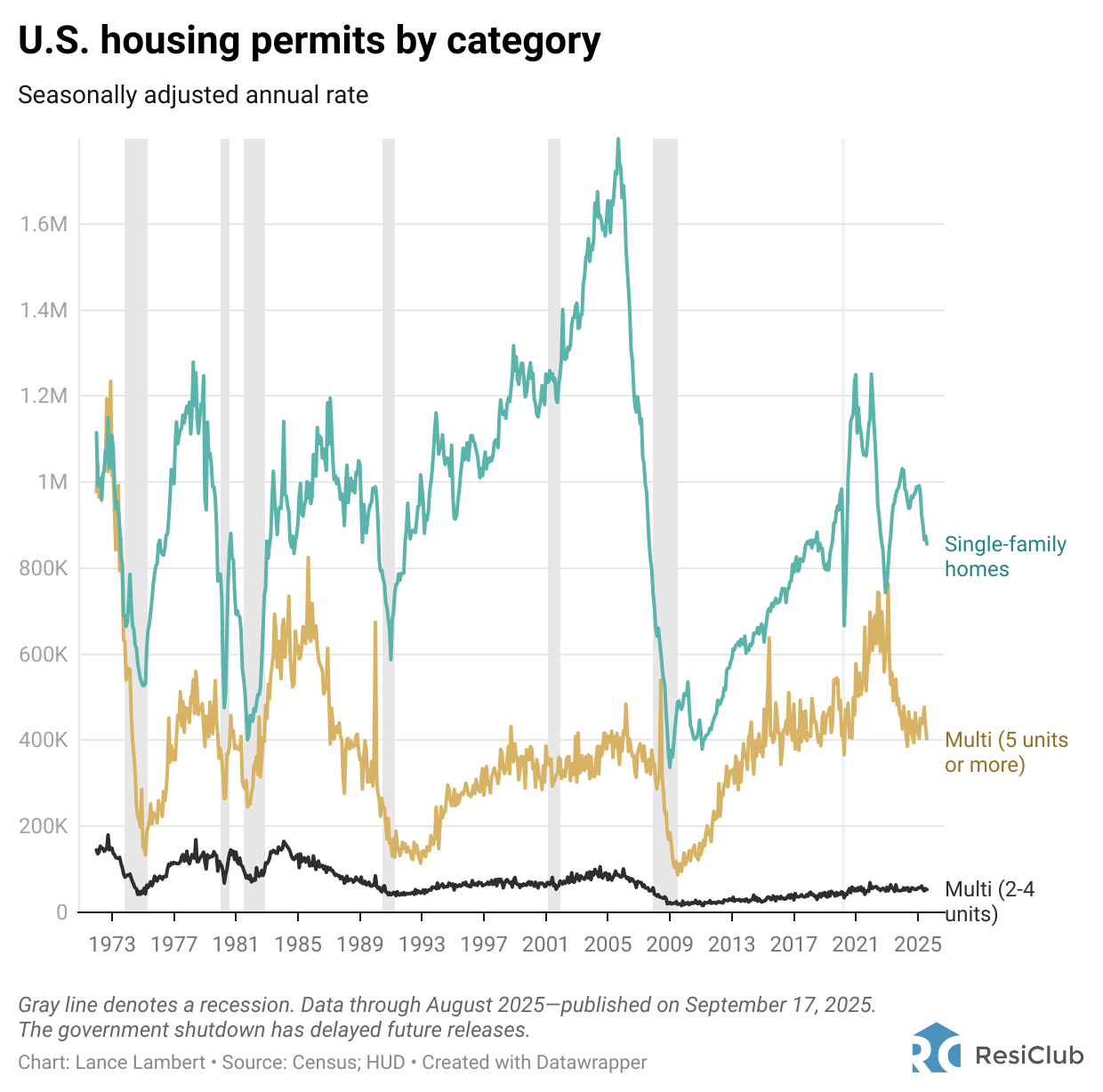

Today, institutional landlords—those owning more than 1,000 homes—remain a relatively small part of the national single-family housing market. They own less than 1.0% of the total U.S. single-family housing stock and have accounted for only about 0.3% of transactions over the past three years. Yet, two decades ago, they didn’t even really exist.

When Blackstone began buying single-family rentals in 2011, there wasn’t a single firm that owned at least 1,000 U.S. single-family homes. By late 2016, Blackstone’s fund, Invitation Homes—which the firm later took public in 2017 and fully exited by 2019—had grown its portfolio to nearly 50,000 single-family rentals. (As of the end of Q3 2025, Invitation Homes wholly owned 86,139 single-family rentals.) Institutional funds buying at the bottom of the housing crash, from 2011 to 2013, marked the birth of the modern institutional single-family rental asset class.

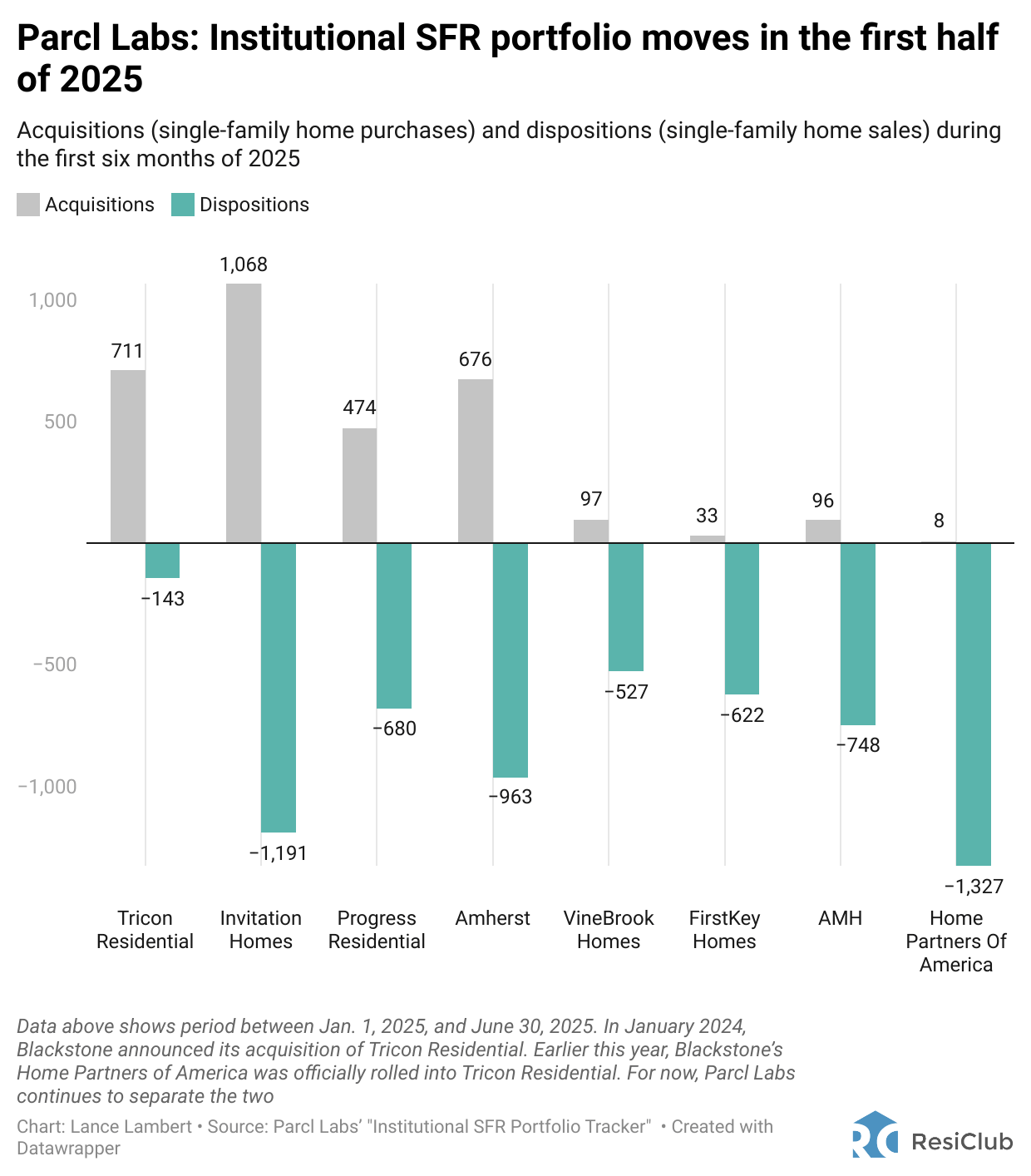

Sean Dobson, CEO of the Amherst Group—which, according to Parcl Labs, owns at least 42,973 single-family rentals—saw that shift firsthand. After the federal government tightened lending, the housing bubble burst, and single-family homes began selling below replacement cost, the government was practically begging institutional capital to step into the market around 2010, believing they could serve as a “shock absorber.” Dobson illustrates the point by noting, “When we [Amherst] first started this [single-family rental] business, we had a handshake to buy 50,000 houses from Fannie Mae in one trade.” While that trade didn’t occur, it illustrates the backdrop at the time.

On Friday, Dobson will be among the speakers at ResiDay 2025—a one-day conference hosted by ResiClub in New York City.

I did a pre-interview with Dobson—we posted the full video on YouTube. Below are some of his key takeaways.

National home prices: Grinding sideways, with affordability as the constraint

Dobson emphasized that the housing market is unlikely to see dramatic national home price swings in the near term. Neither another national boom, nor crash.

He admits there’s some downward pressure on home prices given the affordability environment we’re in, however, there’s not enough resale supply hitting the market to actually manifest a national level crash like 2007-2011.

“Home prices we think would be lower if there are more sellers, obviously. But there's good reason there aren't more sellers, right? So many people got such low interest rate mortgages that at a time when the demand would naturally fall from rising interest rates, rising interest rates also caused the [new listings] supply to fall.”

“I think the overall message is that we're on the lookout for something that changes the velocity of this whole thing and [we] can't find it. We spent a lot of time on the Airbnb guys. I thought those guys might be the weak hands, because it's like, who has to sell? And we have a pretty good model on how supply affects home prices. But even when you just radically change supply, it moves home prices [down] in single digits… we think you're looking at a decade of difficulties for people to get into buying a home.”

“That's why we think we're talking about really a next decade of a lot of demand for rental, because it's the choice of, ‘how do I get the size, how do I get the features that come with that home, like the school location’? And that's how long we think it's going to take for what we would see as sort of long-term depth of some of the standards for affordability to be recaptured, because we think it has to come from income growth. And that's staring in the face of all this business and AI, which [some] people are arguing might be driving [real incomes] down [in the future].”

Dobson: Fixing affordability starts with housing credit reform

The further the Pandemic Housing Boom fades into the rearview mirror—and as national income growth continues to outpace national home price growth—Dobson believes national housing affordability will gradually improve.

That could be sped up, he says, if some of lending tightening done during and following GFC were un-done. His argument isn’t to recreate the reckless lending of the mid-2000s, but to reintroduce responsible credit risk-taking and allow back in some of the lower credit homebuyers that were in the market in, say, the 1980s and 1990s.

In Dobson’s view, if lending were loosened to allow some of those lower credit score homebuyers back into the market, it wouldn’t magically improve affordability overnight; however, it would create a steady stream of housing demand for builders who could produce more lower-end single-family homes—or even manufactured homes—that weren’t built in the years following the Great Financial Crisis. He believes that would improve affordability over time.

“We get consulted by governors, by senior people in the federal government. Everyone kind of wants the playbook: ‘Tell me what to do and I'll fix it.’ And we tell them [to] make more subprime mortgages. And they tend to fold up their notebooks and head on... People are frustrated, right? People are super frustrated because you have this expectation that: ‘I did all these things, and now I should be able to buy a house, and I can't.’ You want to blame somebody, right? And if you see me [Amherst] buying it, well, you're like, well, it must be his fault, so I get it—I think it [that thinking] is dangerous.”

“They [homebuilders] don't have demand [from that lower credit score homebuyers like they used to], and they don't have demand because their customers don't have financing. And they [some sidelined buyers] don't have financing because the mortgage market doesn't take credit risk like [it used to]... So what we [Amherst] provide is a solution today.”

Dobson: Tightened credit boxed out homebuyers and helped draw institutional capital into the housing market

Dobson says the typical Amherst tenant has a credit score too low to qualify for a mortgage in today’s market. Without single-family rental options, many of those households wouldn’t be able to live in the same neighborhoods or school districts they do now, he argues.

That challenge reflects a broader shift in the mortgage market. In Q1 1999, borrowers in the bottom 10th percentile of mortgage credit scores had scores of 597. By Q3 2025, that threshold had risen to 660, reflecting that many lower-credit households had been locked out of homeownership following the bust, Dobson says.

In Dobson’s view, those tighter lending standards—implemented after the housing bust that began in 2006—helped pave the way for institutional investors like Amherst to step in and fill the gap through single-family rentals.

“I sat with Chairman Bernanke, I sat with Yellen, and I begged them to try to get in the way of Dodd-Frank, because I knew what was going to happen, and we lost that. I said, ‘Okay, well, we're going to get these families in these houses some way, and we have a lease and we have financing, we can operate the real estate. So let's get the people in the homes and get their kids in the schools, and then let all the wizards figure out, like, what’s the better solution?’ Because today, there isn't one until someone with a 625 FICO can go borrow money at about the same rate that you and I can borrow at, there isn't a better solution. And so that's, you know, if you want to blame somebody, it's the knee jerk, explainable, but too long in place reaction to the subprime mortgage crisis.”

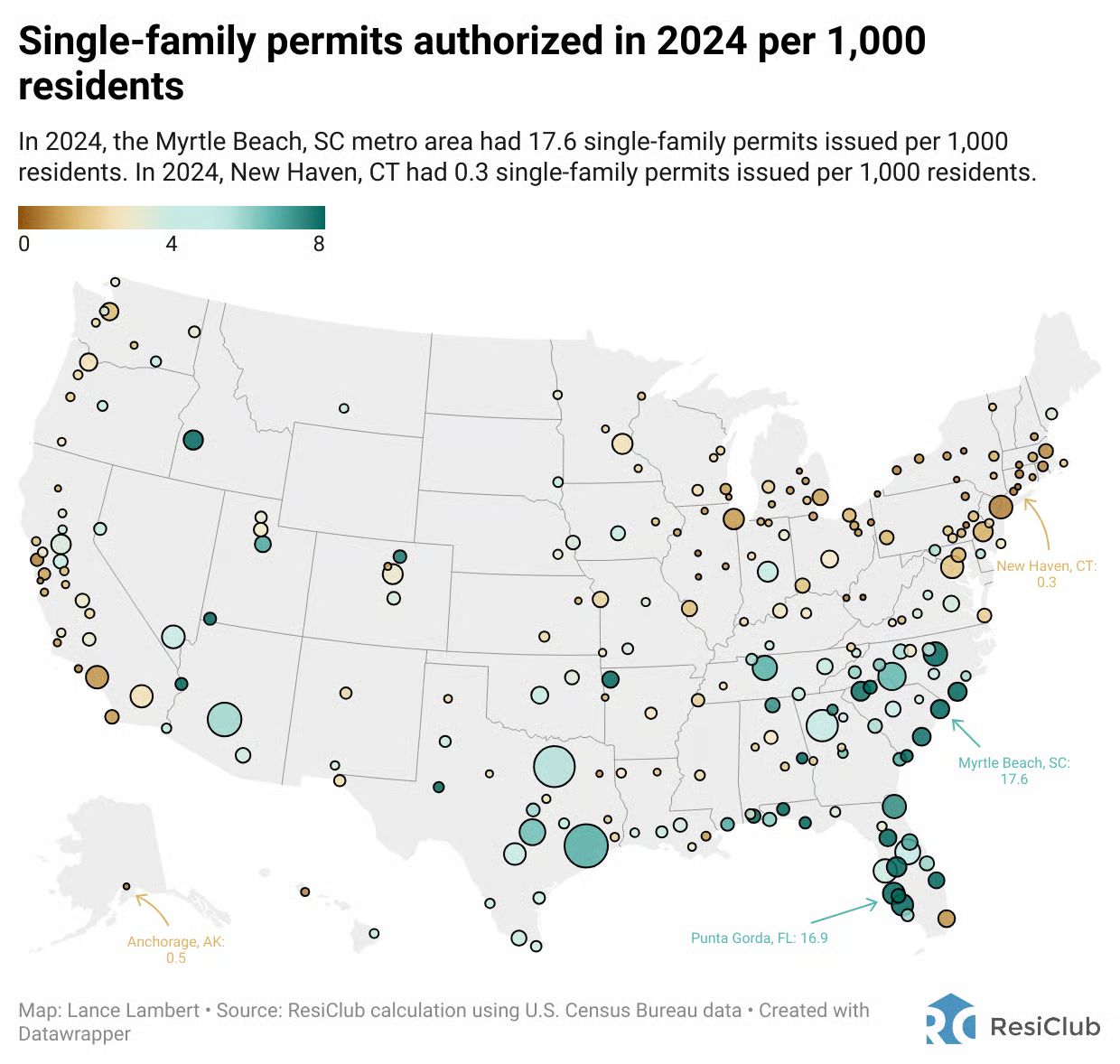

Greater homebuilding activity is helping improve affordability more quickly in Florida and Texas, Dobson argues

During our conversation, I asked him for his thoughts on the current regional housing market variation—specifically, why pockets of Florida and Texas have weakened more than markets in the Midwest and Northeast.

“The common theme amongst the markets that are retracing? So Austin, you mentioned Jacksonville, which is not quite as bad Western Florida—the Tampa Bay area, Cape Coral has been really, been really tough. I would say the common theme is those are places [where] it's pretty easy to build, and as home prices moved above, kind of their construction costs, they naturally kind of tend back down. And so those places, the market did what the market is supposed to do, right? Prices were rising and rising quickly, and homebuilders came in and they built a lot of supply, even in a place like Dallas. So we [Amherst] tend to spend [time looking at local data]—because we're like you [ResiClub], we’re in the housing market [data] all day, every day. So we don't really do that much work on like the ‘U.S. housing market’. We do work on much smaller micro footprints. But if you take a place like Dallas—Dallas overall [in aggregate], seems like it's okay, healthy, not great, [but] not weak. But if you bifurcate the homes by vintage year, and look at their price movements, then Dallas looks a lot like Cape Coral [in certain areas]. The new home construction market [areas] in Dallas looks a lot like Cape Coral. So builders came out—they did, you know, getting land permitted, getting lots of them platted, getting horizontals in all takes time. So there's always a lag between when the housing market really wants to buy the homes and when builders can deliver them. And that oftentimes [it] creates too much supply [at once] trying to squeeze through a channel that [also has] waning demand.”

Institutional single-family homebuying has slowed—could it accelerate again?

At the height of the Pandemic Housing Boom, institutional homeowners—those owning at least 1,000 single-family homes—made up an all-time high of 2.4% of home purchases in Q2 2022, according to John Burns Research and Consulting. That period, at the tail end of the boom, was when yields were particularly attractive as borrowing costs were ultra-low, home prices were soaring, and rents were climbing rapidly. However, since mortgage rates spiked and capital markets shifted, their share has fallen to around 0.3% of transactions over the past three years. The math isn’t as favorable now.

What, if anything, could pull more institutional capital back into the single-family housing market?

“We really think the answer to that question comes in this investor adoption question, right? Will state pension funds allocate and scale to single-family rental?”

“The time that we've had to operate the [single-family] real estate has also made that core investor group aware that you can collect rents [from single-family rentals], you can provide good service, you can operate this as a piece of real estate. That track record is helpful, but the next wave of investing won't come from the same sources of capital [private equity]. It'll come from those core investors [like pension funds] finally saying, ‘You know what, a 5% or 6% cash on cash return that outpaces inflation by 50 plus percent every year has a spot in my portfolio and scale.’”